|

NASA's Spirit Rover is

providing a lesson to aspiring digital photographers:

Spend your money on the lens, not the pixels.

Anyone who has ever agonized over whether to buy a

3-megapixel or 4-megapixel digital camera might be

surprised to learn that Spirit's stunningly detailed

images of Mars are made with a 1-megapixel model, a

palm-sized 9-ounce marvel that would be coveted in any

geek's shirt pocket. Anyone who has ever agonized over whether to buy a

3-megapixel or 4-megapixel digital camera might be

surprised to learn that Spirit's stunningly detailed

images of Mars are made with a 1-megapixel model, a

palm-sized 9-ounce marvel that would be coveted in any

geek's shirt pocket.

Spirit's images are IMAX quality, mission managers

say.

The word pixel is derived from the term "picture

element." A pixel is the smallest dot of

information that goes into making a digital image. One

megapixel is a million pixels set up in an array equal

to 1,000 by 1,000.

Intuitively, more pixels means higher resolution.

That's generally true on a display screen. But when

capturing images, where a pixel is more properly called

a sensor, the count is just one of many factors that

control quality.

Seeking perfection

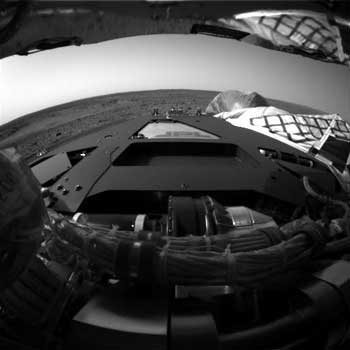

The technology used to make Spirit's Panoramic

Camera, or Pancam, is essentially the same as what goes

into a Casio or Pentax digital camera.

But the Pancam's lenses -- there are two, which

provides stereo imaging capability -- are crafted more

finely than anything you'd probably want to plunk down a

Visa for. And the light-capturing chunk of silicon,

called a charged coupled device, or CCD, was

manufactured with no tolerance for the minor flaws that

are inherent in mass-produced consumer cameras.

Perhaps most important, the sensors on Spirit's CCDs

are bigger, explained Patrick Myles, director of

corporate communication at the Dalsa Corporation, which

built the CCDs for all of the rover's cameras (Spirit

has nine altogether, including hazard avoidance cameras

and a microscopic imager).

A Sony DSC-F717, with a street price of around $600,

has 5.2 million sensors (or 5 megapixels) on a chip that

is 8.8 by 6.6 millimeters (or .35 by .26 inches). The

Pancam has just a million sensors spread across a chip

that's 12 by 12 millimeters -- nearly a half-inch

square. A Sony DSC-F717, with a street price of around $600,

has 5.2 million sensors (or 5 megapixels) on a chip that

is 8.8 by 6.6 millimeters (or .35 by .26 inches). The

Pancam has just a million sensors spread across a chip

that's 12 by 12 millimeters -- nearly a half-inch

square.

Each tiny Pancam sensor, measured in microns, is

nearly four times as big as those on the Sony.

In the consumer market, which Dalsa does not target,

5-megapixel cameras often use the same size CCD as a

3-megapixel camera. More pixels are simply crammed onto

the same-size chip.

"The pixels themselves get smaller," Myles

said. "This has an impact on image quality."

Why? For one thing, smaller pixels are less

light-sensitive.

Also, the lens quality might not support the

additional pixels. As the receptors get smaller, a

higher quality lens is needed to properly focus light

onto each pixel. So where each pixel ought to capture

different light information -- say perhaps a subtle

shading change on the subject's cheek -- the same

information can get spread across several pixels after

passing through a lower quality lens.

20-20 vision

The Pancam was conceived at Cornell University and

built at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Dalsa, based

in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, makes cinema-quality video

components and other high-end imaging devices and was

called on to make the CCDs for the Pancam and the other

cameras on Spirit and its twin rover, Opportunity. The Pancam was conceived at Cornell University and

built at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Dalsa, based

in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, makes cinema-quality video

components and other high-end imaging devices and was

called on to make the CCDs for the Pancam and the other

cameras on Spirit and its twin rover, Opportunity.

"They are the world's highest performing chips

in terms of light sensitivity and chip quality,"

Myles said in a telephone interview earlier this week.

Overall, how does a Pancam stack up to the typical

5-megapixel camera you might purchase at Best Buy?

"There really isn't any comparison," Myles

said.

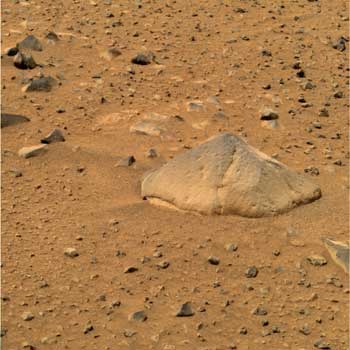

NASA officials say the

camera shows what a human with 20-20 vision would see on

the surface of Mars. But anyone who has zoomed

in on a distant

rock in one of Spirit's color pictures would have to

wonder if perhaps Superman's vision might be a better

comparison.

Experts argue endlessly about what the human eye can

actually see, however. Comparing human vision to what a

camera captures "is really up to great

speculation," Myles said.

NASA's analogy, Myles explained, is "probably a

bit of marketing spin. It helps people visualize the

quality." The height and breadth of a Pancam image

is roughly equal to what a person would see, taking into

account peripheral vision. And the Pancam has a human

perspective. It sits atop a mast on the rover, 5 feet

(1.4 meters) above the surface.

Myles said the actual

image quality probably exceeds human capabilities,

especially after the image is processed and a computer

is used to provide a zoom

function.

Tricks with light

The Pancam does not make

a color picture directly. Instead, it records light

versus dark in shades of gray. As with other CCD cameras

used in high-end astrophotography, such as on the Hubble

Space Telescope,

a series of filters are applied to gather multiple

images that are then blended together.

In the most basic application of this process, three

images are gathered of a scene, one each recording red,

green and blue light. Those are then put together with

special software to create a color picture.

A consumer digital camera uses a single coated filter

to make the transition from photon reality to electrons

and then digital information.

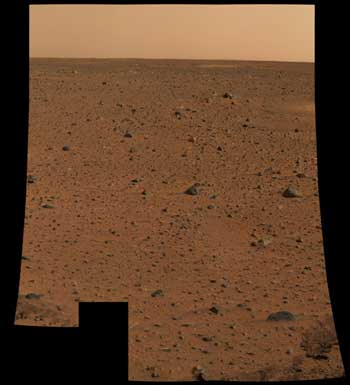

Additionally, the Pancam

swivels 360 degrees around and 90 degrees up or down, so

that individual scenes can be stitched together to

create a view of the rover's entire

surroundings. The

pictures are expected to reveal important geologic

details about rocks, and they're also used for

navigation and to pick distant science targets.

Modern Ansel Adams

Spirit's pictures are said to be three times sharper

than those of the 1997 Mars Pathfinder mission or the

1970s Viking landers.

The Viking missions, as well as the Voyager missions

to the outer planets, used technology similar to

antiquated television vacuum tubes. CCD technology was

first developed in 1969, but it took decades before

arrays were big enough to be useful.

Much of the research that ultimately led to today's

commercial digital cameras was funded by NASA. A first

major step was in developing an 800 by 800 pixel array

-- less than a megapixel -- which is what's in the

Hubble telescope.

The Pancam results so far have mission managers

ecstatic. Cornell astronomer James Bell, who led the

development of the camera, called the first Spirit

pictures "absolutely spectacular."

Nobody has argued with him.

In fact, Steven Squyres, a Cornell professor who

directs the rover science team, called Bell "the

Ansel Adams of the Space Age."

|